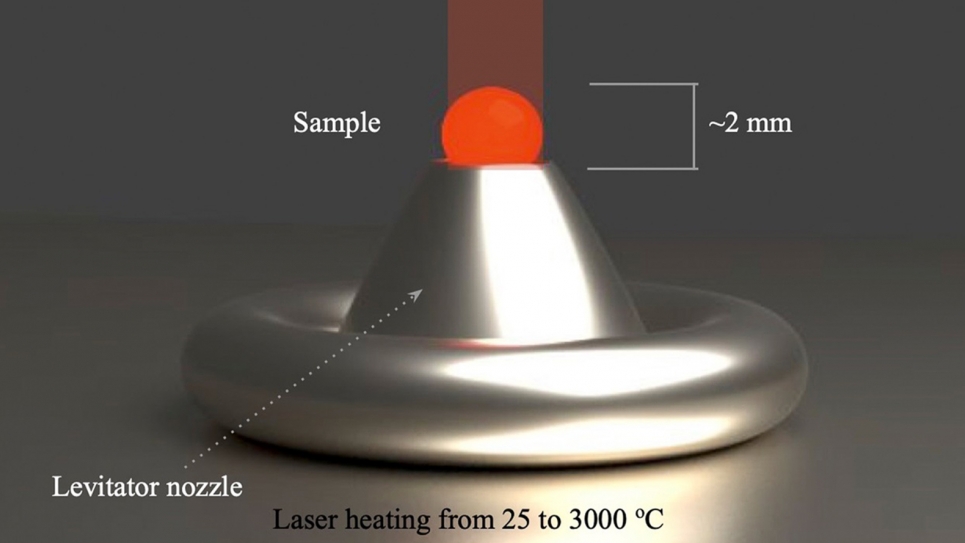

“We have a nozzle connected to a flow of inert gas, and as it suspends the sample, a 400-watt laser heats the material from above,” Gallington said. “You need to tinker with the gas flow to get it to levitate stably. You don’t want it too low, because the sample will touch the nozzle, and might melt to it.”

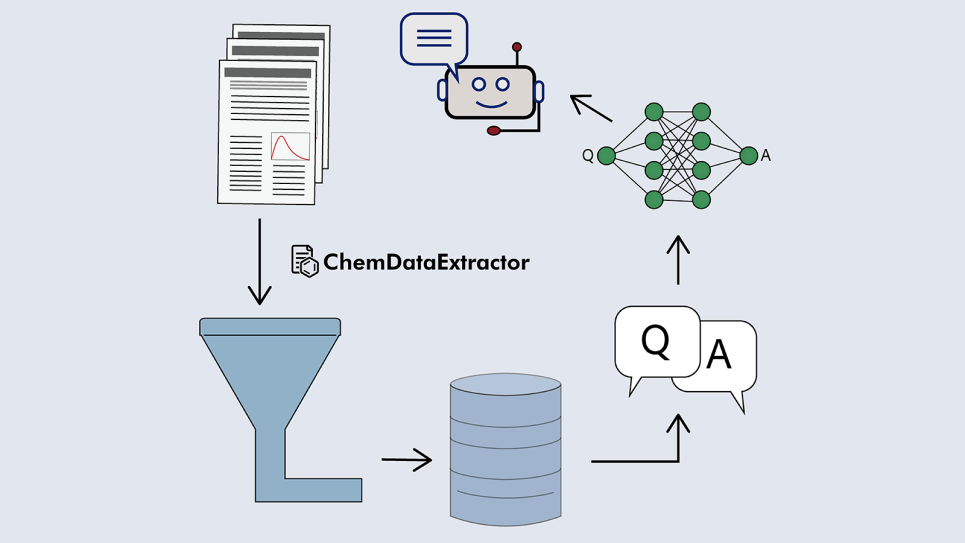

Once the data were taken and beamline scientists had a good understanding of some of what happens when hafnium oxide melts, the computer scientists took the ball and ran with it. Sivaraman fed the data into two sets of machine learning algorithms, one of them that understands the theory and can make predictions, and another — an active learning algorithm — that acts as a teaching assistant, only giving the first one the most interesting data to work with.

“Active learning helps other kinds of machine learning to learn with fewer data,” Sivaraman explained. “Say you want to walk from your house to the market. There may be many ways to get there, but you only need to know the shortest path. Active learning will point out the shortest way and filter out the others.”

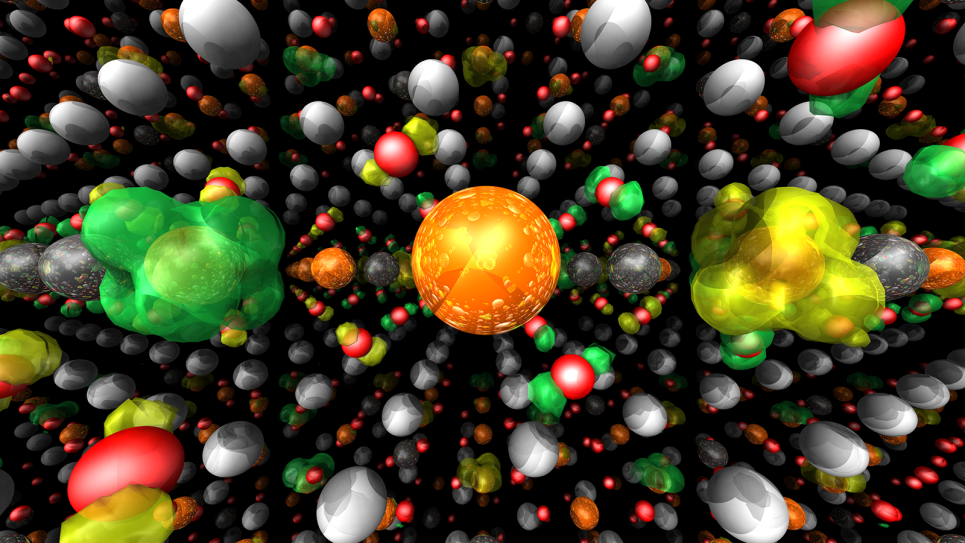

Computations were run on supercomputers at the ALCF and the Laboratory Computing Resource Center at Argonne. What the team ended up with is a computer-generated model based on real-life data, one that allows them to predict things the experimentalists didn’t — or couldn’t — capture.

“We have what is called a multi-phase potential, and it can predict a lot of things,” Benmore said. “We can now go ahead and give you other parameters, such as how well it retains its shape at high temperatures, which we did not measure. We can extrapolate what would happen if we go beyond the temperature we can reach.”

“The model is only as good as the data you give it, and the more you give it the better it becomes,” Benmore added. “We give as much information as we can, and the model becomes better.”

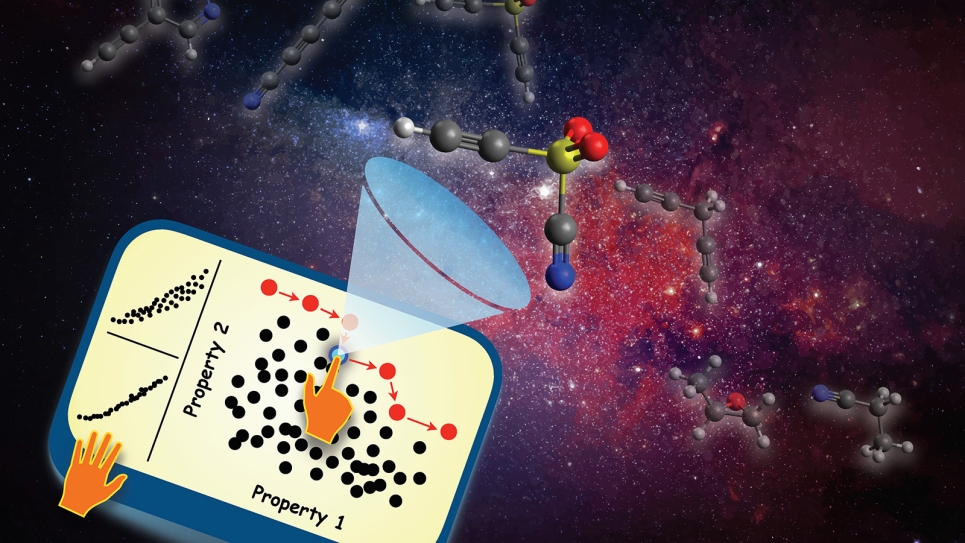

Sivaraman describes this work as a proof of concept, one that can feed back into further experiments. It’s a nice example, he said, of collaboration between different parts of Argonne, and of research that could not be done without the resources of a national laboratory.

“We will repeat this experiment on other materials,” Sivaraman said. “Our APS colleagues have the infrastructure to study how these materials melt at extreme conditions, and we are working with computer scientists to build the software and streaming infrastructure to rapidly process these datasets at scale. We can incorporate active learning into the framework and teach models to more efficiently process the data stream using ALCF supercomputers.”

For Stan, the proof of concept is one that may replace the necessary tedium of people working out these precise calculations. He has watched this technology evolve during his career, and now what once took months only takes a few days.

“I’m not saying humans aren’t great,” he chuckled, “but if we get help from computers and software, we can be greater. It opens the door for more experiments like this that advance science.”

==========

The Argonne Leadership Computing Facility provides supercomputing capabilities to the scientific and engineering community to advance fundamental discovery and understanding in a broad range of disciplines. Supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Office of Science, Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) program, the ALCF is one of two DOE Leadership Computing Facilities in the nation dedicated to open science.

About the Advanced Photon Source

The U. S. Department of Energy Office of Science’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive X-ray light source facilities. The APS provides high-brightness X-ray beams to a diverse community of researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. These X-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being. Each year, more than 5,000 researchers use the APS to produce over 2,000 publications detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other X-ray light source research facility. APS scientists and engineers innovate technology that is at the heart of advancing accelerator and light-source operations. This includes the insertion devices that produce extreme-brightness X-rays prized by researchers, lenses that focus the X-rays down to a few nanometers, instrumentation that maximizes the way the X-rays interact with samples being studied, and software that gathers and manages the massive quantity of data resulting from discovery research at the APS.

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation’s first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America’s scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.