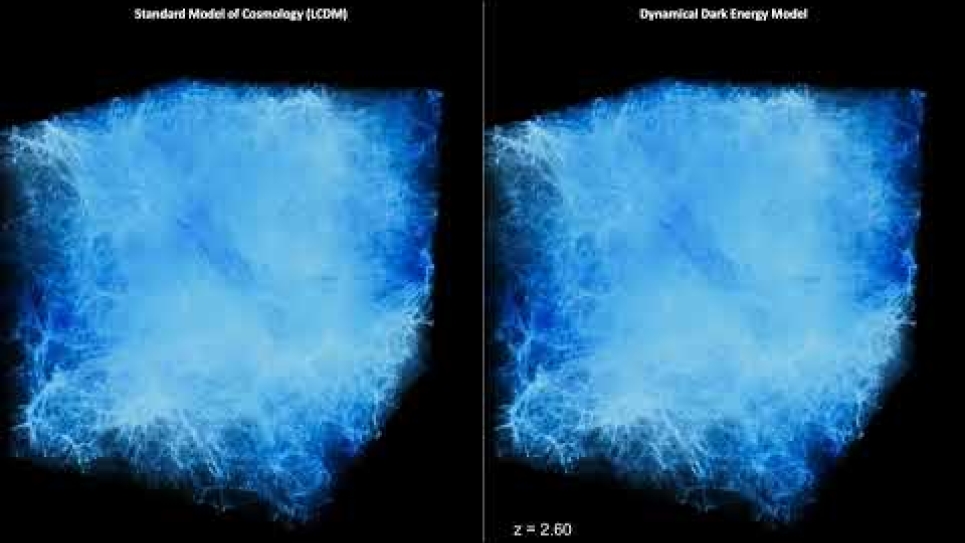

“The idea is that you create a model universe under one set of assumptions, and then you compare your model universe to the real universe. If the agreement is very good, it gives you some confidence that your assumptions are correct,” Hearin said. “But if you have some gross discrepancy, then it tells you that your assumptions don’t align with the real universe and don’t represent the truth.”

While simulations can’t directly confirm DESI’s findings, they provide a critical feedback loop between theory and observation. By testing different measurements within the simulations, researchers can refine their analysis techniques and assess whether the observed patterns could emerge from systematic effects rather than new physics.

“If looking at these two simulations gives us an idea of the type of measurement we should make to help us narrow in on a cosmological model, then we can go back to the real DESI data and make that same measurement and see what it tells us,” Beltz-Mohrmann said.

Bringing the universe into focus with Aurora

The scale and complexity of running massive cosmological simulations at high resolution over vast volumes can lead to long runtimes, but Aurora allowed the team to complete them quickly.

“Using Aurora’s immense processing power to rapidly run large-scale simulations at sufficiently high resolution, we can respond much faster to new insights from cosmological observations,” said Argonne computational scientist Adrian Pope. “These simulations would have taken weeks of compute time on our earlier supercomputers, but each simulation took just two days on Aurora.”

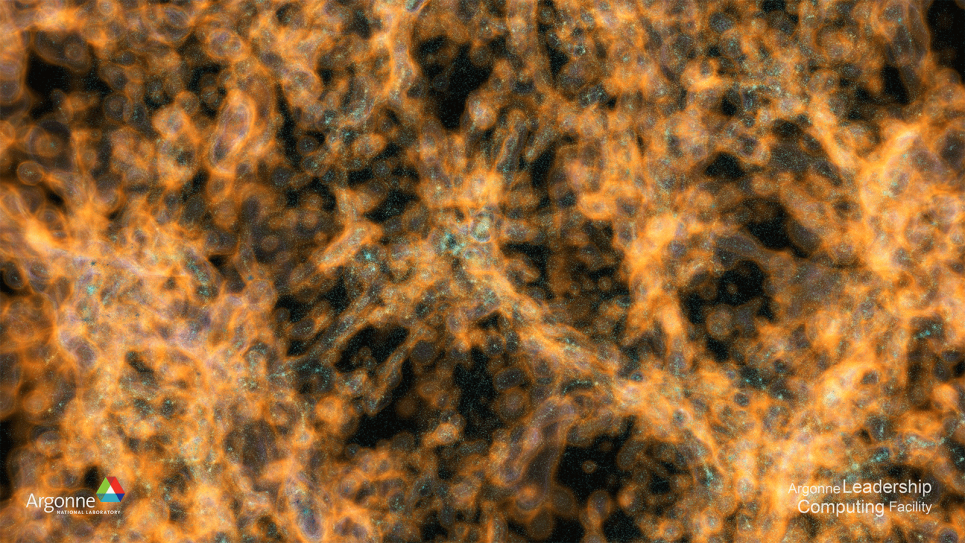

Achieving high resolution was particularly critical for this study, as Heitmann explained: “Aurora is extremely important because to detect these fine differences, we need incredibly high resolution in our simulations. Without that level of resolution, details can get washed out. Think of it like taking off your glasses and trying to make out a blurry figure.”

To further accelerate their work, the team employed a method called on-the-fly analysis, which allowed them to process simulation data as it was being generated. This approach eliminated bottlenecks in storing and post-processing simulation data, leveraging Aurora’s power to extract insights faster and refine simulations in real time.

“This pair of simulations really illustrates our ability to take a result that’s hot off the presses from a collaboration like DESI, immediately run a simulation based on those results, and then see what it looks like,” Beltz-Mohrmann said.

While DESI’s findings continue to be scrutinized, the team’s simulations provide a valuable tool for refining analysis techniques and exploring new ways to interpret the data. To enable additional studies, the team has made the simulation data publicly available.

“This is a new caliber of simulations in the field,” Hearin said. “Essentially, it provides the community with a test bed to try out ideas for distinguishing between these two universes. The simulations can offer insight into how we might use DESI data to determine which of these competing models of dark energy is the truth.”

The team detailed their work in the study, “Illuminating the Physics of Dark Energy with the Discovery Simulations.”

DESI is supported by the DOE Office of Science. The Argonne team, including Heitmann, Hearin, Beltz-Mohrmann, Pope, Alex Alarcon, Michael Buehlmann, Nicholas Frontiere, Sara Ortega-Martinez, Alan Pearl, Esteban Rangel, Thomas Uram, and Enia Xhakaj, performed the simulations with support from the ALCF’s Aurora Early Science Program and DOE's Exascale Computing Project. Their work was also partially supported by DOE’s Scientific Discovery through Advanced Computing (SciDAC-5) program and NASA’s OpenUniverse project.