Simulations Bolster Parkinson’s Theory

Scientists have used powerful computational tools and laboratory tests to discover new support for a once-marginalized theory about the underlying cause of Parkinson’s disease.

Previously, the dominant theory was that insoluble intracellular fibrils called amyloids cause Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. The new findings, which are in direct conflict with the amyloids theory, provide a step-by-step explanation of how a “protein-run-amok” aggregates within the membranes of neurons and punctures holes in them to cause the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

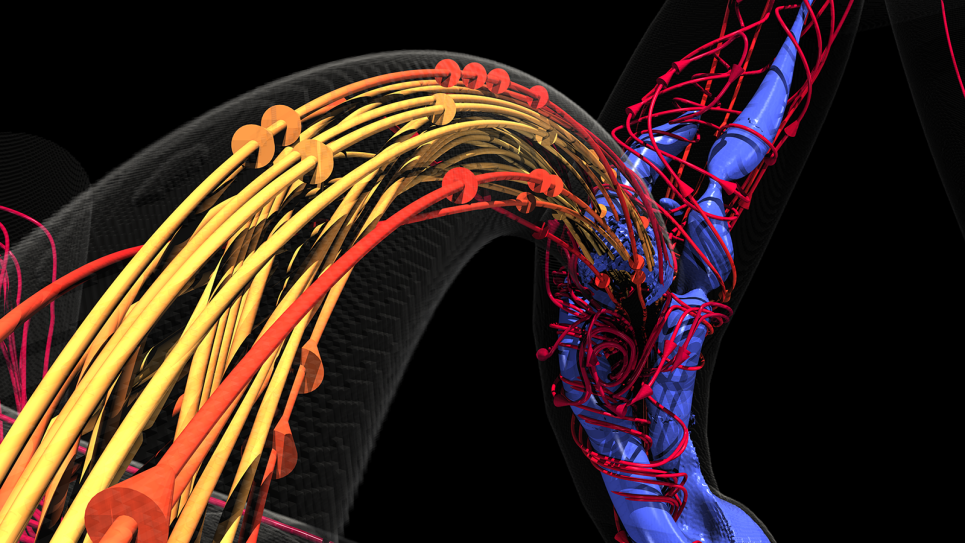

The discovery, published in the March 2012 issue of the FEBS Journal, describes how α-synuclein (α-syn) can turn against us, particularly as we age. Results from computational models run at the San Diego Supercomputer Center explain how α-syn monomers penetrate cell membranes, become coiled, and aggregate in a matter of nanoseconds into dangerous ring structures that spell trouble for neurons.

“The main point is that we think we can create drugs to give us an anti-Parkinson’s effect by slowing the formation and growth of these ring structures,” said University of California, San Diego researcher Igor Tsigelny, lead author of the study. Using funding from the US Department of Energy and National Institutes of Health, Tsigelny led a team of researchers from departments across UCSD and SDSC to make the discovery. The experimental validation studies were performed by neuroscientist and pathologist Eliezer Masliah, and his associates, who relied on 3-D models of proteins, plus molecular dynamics simulations of the proteins, other modeling techniques, and cell-culture experiments.

Familial Parkinson’s disease is caused in many cases by a limited number of protein mutations. One of the most toxic is A53T. Tsigelny’s team showed that the mutant form of α-syn not only penetrates neuronal membranes faster than normal α-syn, but the mutant protein also accelerates ring formation.

“The most dangerous assault on the neurons of Parkinson’s patients appears to be the relatively small α-syn ring structures themselves,” Tsigelny said. “It was once heretical to suggest that these ring structures, rather than long fibrils found in neurons of people having Parkinson’s disease, were responsible for the symptoms of the disease; however, the ring theory is becoming more and more accepted for this neurodegenerative disease and others such as Alzheimer’s disease. Our results support this shift in thinking.”

The modeling results also are consistent with the electron microscopy images of neurons in Parkinson’s disease patients; the damaged neurons are riddled with ring structures.

These conclusions about the role of ring structures have spawned an intense hunt at UCSD for drug candidates that block ring formation in neuron membranes. The sophisticated modeling required involves a complex realm of science at the intersection of chemistry, physics, and statistical probabilities. A kaleidoscope of interacting forces in this realm makes α-syn proteins bump and tremble like they’re in an earthquake, coil and uncoil, and join together in pairs or larger groups of inventive ballroom dancers. To do these computationally challenging calculations, the team used Argonne National Laboratory's IBM Blue Gene high-performance computing system in addition to the computational resources offered by SDSC.

The modeling is creating a much better understanding of the mysterious α-syn protein itself, according to Tsigelny. A few years ago the protein was shown to accumulate in the central nervous system of patients with Parkinson’s disease and a related disorder called Dementia with Lewy bodies. Today, these results show precisely how two α-syn proteins insert their molecular toes into the membrane of a neuron, wiggle into it in only a few nanoseconds, and immediately join together as a pair. The pair isn’t itself toxic; however, when more α-syn proteins join the dance, a key threshold is eventually crossed; polymerization accelerates into a ring structure that perforates the membrane, damaging the cell.

Tsigelny said many ring structures may be required to actually kill neurons, which are known for their durability. The nerve cells may be able to repair dozens of ring-induced perforations, keeping pace with α-syn assault. But at some point, the rate of perforations surpasses the ability of neurons to repair them. As a result, symptoms of Parkinson’s disease gradually appear and worsen.

“We think we can create a drug that stops the α-syn polymerization at the point of non-propagating dimers,” Tsigelny said. “By interrupting the polymerization at this crucial step, we may be able to slow the disease significantly.”

Given their deeper understanding of α-syn polymerization in neurons, they are now focused on understanding how monomers of α-syn stick to one another. Their search for drug candidates will include molecules that induce different conformations of α-syn proteins that are less inclined to stick together. Tsigelny said this effect, even if small, could reduce symptoms.

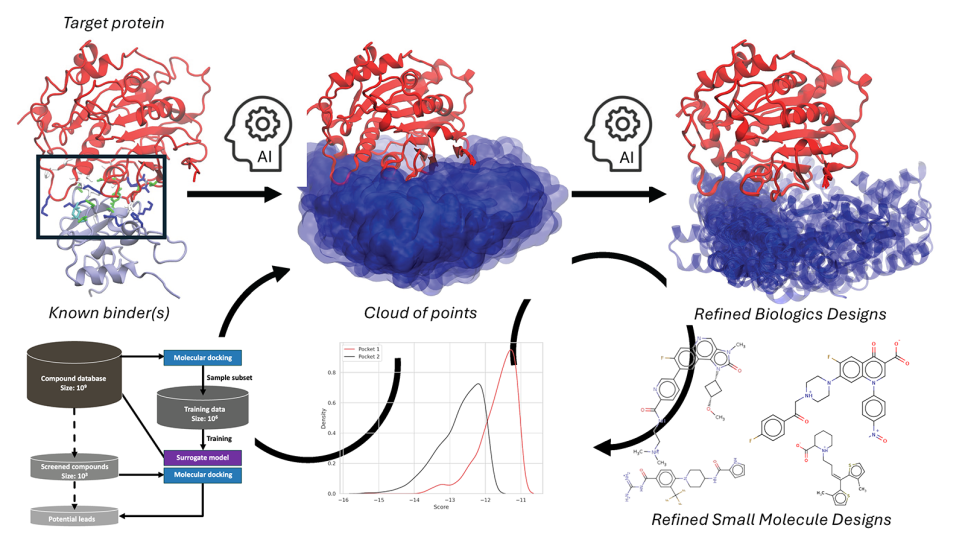

This computationally intensive approach includes an examination of the many possible three-dimensional arrangements of α-syn dimers, trimers and tetramers. Pharmaceutical companies have used versions of the approach to develop drug candidates designed to bind to ‘anchor residues’ or ‘hot spots’ within target proteins. Algorithms assess in virtual experiments the theoretical ability of thousands of candidate drugs to bind to human proteins in the ever-expanding database of known 3-D structures of those proteins.

However, attempts to find drugs this way have generated promising candidates that fail in clinical trials with expensive regularity.

“Out of these failures we’ve come to appreciate that proteins change their shapes so often that what would appear to be a primary drug target may be present one nanosecond, gone the next, or it wasn’t relevant in the first place,” said Tsigelny, a physicist-turned-drug-designer.

Tsigelny’s approach takes advantage of classical drug-discovery algorithms, but adds additional analytical techniques to expand the search to include how a target protein’s conformations change in response to the forces operating on the scale of molecules.

“Sometimes, the drug-discovery models, despite being ‘nice looking,’ can be completely wrong,” Tsigelny said. “Scientists involved in drug discovery need to know when and to what extent to trust them. Even a slight shift in a cell’s environment can profoundly change the interactions of proteins with neighboring molecules. We think it’s realistically possible to design a drug to treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and other diseases like diabetes with a more fundamental understanding of the proteins involved in those diseases.”

A version of this story first appeared on the SDSC website.